Figure 1

To find out some aspects of abridged translations, I used Fennica 1993:3, the national bibliography of Finland, on CD-rom. By using search words like "lyhentäen", "lyhennetty", and "lyh.", I searched for the abridged translations. After retrieving the information, I deleted all those entries which contained the search word, but were not abridged translations. I found 218 translations in total during the time period of 1960-1993. The amount of books mentioned was 345 due to reprints. Some of the abridged translations may have been left out, if the entries in Fennica had spelling errors or the abridgement was not stated. However, this was the only way to find the abridgements.

I used dBase III+ to create a database which enabled me to study the data. I did not include in the database the "Kirjavaliot" published by Valitut Palat for reasons I will explain later (see chapter 2.8).

The amount of data is so small that it was not always possible to draw any conclusions, only to present some possible explanations. I will present my findings and my interpretations of them in this chapter. All figures refer to the data I collected unless otherwise stated. I use percentage figures, because they are more useful in comparisons. However, it is good to keep in mind that the smallest percentages may refer to just one or two books, so they are not as reliable as they would be with a larger amount of data.

The entries for the books I will mention as examples can be found in appendix 1. For each book I have chosen the most recent printing. The number of reprints given is not necessarily the same as the number of entries in Fennica, because some of the translations have been made before 1960, and sometimes one entry contains data about several reprints. In the database I created, every single printing has its own entry.

There are some difficulties in trying to categorize abridged translations, because there are many ways of making the abridgement. Most of the translations are easy to put into one category or another, but there are borderline cases in which you just have to decide which category to choose. Also making the categories is difficult, because you can not make very many of them or they will just blur the results, not make them clear. So you have to combine the types which are similar enough to create a logical category.

One of the problems with Fennica was missing information. There were some entries which did not state the source text, translator, or publisher. Another matter of concern was the reliability. Because it was impossible to check if the entries in Fennica were correct or not, I just had to rely on what they said about the abridgement method used.

In table 409 of "Suomen tilastollinen vuosikirja 1992" (p. 443), from now on referred to as STV, there are the amounts of translations published during the time period of 1960-1990. The table does not have data about all the years. The years included are 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, and 1990. To put the phenomenon in the right proportions, I used these figures and the data I had collected to count the percentage share of the abridged translations. The percentage varied between 0.41% and 1.83%, the average being 0.99%. So, the impact of this phenomenon is not very great.

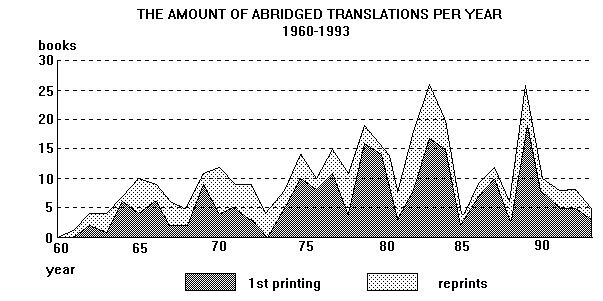

Figure 1 shows the amount of abridged translations per year.

Figure 1

It has grown over the years, but as the amount of all translations has also grown - from 582 in 1960 to 1562 in 1990 (STV:443) - this does not indicate that shortening translations was more popular for example in 1980's than it was in 1960's. In fact, the opposite seems to be true. The percentages from 1985 to 1990 were lower than percentages from 1965-1980 with one exception: 1989, for which the explanation is in the next paragraph. It seems that the amount of abridged translations decreased at the beginning of 1990's. The figures have been low on some previous occasions, like 1973 and 1981, but the period from the 1989 peak to 1992 shows a substantial decrease. No conclusions can be made from the 1993 figure, because I used Fennica 1993:3 which did not have all books published that year.

There are three distinct peaks in the first printings in the chart: 1979-80, 1983-84, and 1989. For two of these there is at least a partial explanation. In 1983 there were 10 translations of children's books made by Meri Starck for a children's book club. If you leave these out, there is no peak in 1983. The 1989 peak is due to 9 books published by Base-Beat in a series of children's books, which have a cassette with them. Without these the peak would be much lower. So there are only two real increases in the amounts of books published: in 1979-80 and in 1984. I use the term "real increase" in the sense that publishers are different, the books are not connected in any way, and the translators are different.

I could not find any reason for the real increases. All the factors I studied (publisher, language, subject, translator etc.) varied, and there was no common factor. One point I noticed is that the years following the peaks (1981, 1985) have a very low figure. So maybe the publishing of these translations has somehow just accumulated by coincidence. With larger amounts of data, the variations from year to year would probably be less distinct. With the current data, even 2 or 3 translations can make a significant difference. If you calculate the average figures for 1979-81 and 1983-85, the curve will become much more stable.

I have only used the amounts of titles when calculating the amounts of translations. However, the sizes of printings would also tell something about the general acceptability of abridged translations. In this study, I have only taken account of the number of reprints, which reveals the same aspect.

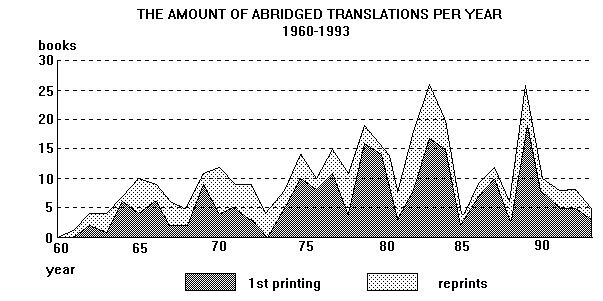

In publisher distribution chart (Figure 2) "first printing" shows the percentage share of translations for the 65 publishers who have published abridged translations.

The 6 publishers in the first printing chart who together have a 5% share are: Kirjatoimi, Neuvostoliittoinstituutti, Otava, Päivä, Semic, and Valtion painatuskeskus. The 8 publishers in the "others" section of the reprint chart are: Gummerus, Kuva ja sana, Käyttökirjat, Otava, Suomen antroposofinen liitto, Suomen raamattuopiston kustannus, Työväen sivistysliitto, and Yleisradion ammattiopisto. Abbreviations: W+G= Weilin+Göös, SSK= Suuri Suomalainen Kirjakerho.

Figure 2

I have shown separately only those publishers who have published 4% or more of the translations. In the parts which show combined figure for several publishers, the percentage share is same for each publisher. For example the 10% share of 5 publishers means that each publisher has published 2% of the translations. This arrangement makes the chart easier to read than it would be if the small percentage shares were all shown separately. The dark line separates those under 4% from those over it.

As can be seen from the chart, 61% of the translations have been published by 8 publishers. So these are the biggest publishers of this kind of translations. Book publishing statistics collected by Liiketalous-tieteellinen tutkimuslaitos (1984-86, appendix 4) list the 7 major book publishers in Finland. The list is somewhat different from the chart: Gummerus, Karisto, Kirjayhtymä, Otava, Tammi, and Weilin+Göös. Of these Gummerus, Otava, and Weilin+Göös have a very small percentage share of the abridged translations. This is why it should be remembered that these figures are valid only for abridged translations - they do not tell anything about the other publishing activities of these publishers.

"Reprints" shows the distribution of reprints between publishers. The reprints include also reprints of abridged translations published before 1960, so their first printings are not included in the first printing chart. The amount of these books is small, except for WSOY as I will explain later. The system is otherwise the same as in the first printing chart. It is interesting to notice that 83% of the reprints have been published by 4 publishers. In all, there are 20 publishers included in this chart. The figure is low because of the 41 publishers who have published one translation, only 4 have published reprints. One explanation for this could be the nature of these publishers and the books they publish. The books can be about some subject in which only a certain small part of the population is interested in, so there maybe is no need for reprints, or the publisher could be small, possibly some organization, religious community etc. which does not have the resources to take reprints.

Another interesting point is WSOY's very large share of the reprints. The 58% share includes books of which there is no first printing in the first printing chart. Their share is 12%, which leaves WSOY still with 46% of the reprints of the books included in the first printing chart. This indicates that WSOY publishes relatively less of these shortened translations, but reprints them more often. One explanation could be the choice of books. Major publishers probably tend to publish best sellers and classics, so they can reprint them in large quantities and get them sold as well. These examples of WSOY's books seem to support this view: Bradford: Rahan ruhtinatar (9 printings), Cooper: Viimeinen mohikaani (7 printings), Dumas: Monte Criston kreivi (9 printings), and Montgomery: Kotikunnaan Rilla (8 printings). Other publishers showing this same tendency are Karisto and Valistus.

Quite an opposite case is Kirjayhtymä, which has published 14% of the first printings but only 6% of the reprints. A partial explanation could be the fact that 84% of the books it has published are non-fiction, which is not reprinted quite as often as fiction, at least not when it is a question of abridged translations (66% of the reprints are fiction, the same figure for first printings is 49%). Without knowing the distribution between fiction and non-fiction Kirjayhtymä publishes, it is difficult to say if it just publishes more non-fiction, or if it tries to avoid shortening fiction. One publisher who does seem to avoid shortening fiction is Tammi. It has published only one such translation, and that was a slightly abridged version of Shakespeare's Hamlet made for the Tampere theater. The rest of its abridged translations are non-fiction.

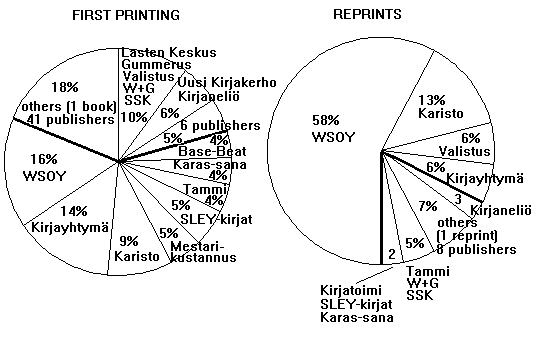

Both of the language charts (Figure 3) show the predominance of English language, which is not surprising considering the amount of English literature published - 55% of all translations on average for the years mentioned in chapter 2.3 (STV:443).

The "others" section in the first printing chart includes Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Hungarian, Japanese, Polish, and the "not known" group.

Figure 3

A slight surprise was the second largest language in translations: German. It would be interesting to have the same information about all the translations published in Finland, because it would make comparisons possible, but unfortunately German belongs to the group "other languages" in the STV table. Either German really is the second largest source language, or for some reason shortened translations have been made from it more frequently than from for example Swedish, which I really expected to be the second largest.

In the reprints chart there are only ten languages, compared to 14 in the first printing chart. The missing ones are Czech, Estonian, Spanish, and Dutch. There are cases in which there was no mention of the source text in Fennica, or in which it was impossible to know what the source language was. For example, Eareckson's "Joni" is one of these. These are in the section "not known" in reprints chart, and in the group "others" in the first printing chart.

There are two quite striking differences between the two charts. First, only 7% of the translations are made from French, but the reprints of these have 18% share in the reprints chart. One possible explanation can be seen from these examples of reprinted books: Dumas: "Monte Criston kreivi" (9 printings), Berteaut: "Jumalani, kuinka olen elänyt" (biography of Edith Piaf, 6 printings), Hugo: "Kurjat" (11 printings), plus several reprints of Verne's books. Secondly, for some reason the percentage share of German language falls from 21% in the first printings to 5% in the reprints. The books translated from German did not include same kind of classics and best sellers as those translated from French. This can have some effect on the amounts of reprints. The percentage shares of reprintings can also be significantly influenced by one book or writer. For example, the increase in the share of Italian language is due to the reprints of Guareschi's books (see appendix 1).

I have divided the translations into five categories according to the method used:

1) abridged translations,

2) abridged and edited translations,

3) translations made from abridged texts,

4) translations where shortening and translating have been done by different Finnish persons,

5) translations made from translations.

I have also divided the publishers into three groups to help finding the possible correlations. The groups and their collective percentage shares are (see figure 2):

1) publishers whose share of the translations is 4% or more, 61%,

2) publishers who have published more than one book, but who have under 4% share, 21%,

3) publishers who have published only one book, 18%.

The most often used method is simple shortening, that is, just leaving out parts of the source text during translation. 72% of the translations are of this kind. This category includes all kinds of books. The distribution between fiction (48%) and non-fiction (52%) is approximately the same as the figure for all translations (49% fiction, 51% non-fiction). Also the source language distribution is equal to the one in figure 3, and the shares of the publisher groups are approximately equal to their shares of all translations.

Abridging and editing means that in addition to shortening, the text has been changed in some other way. For example the translation has been adapted to suit the Finnish culture and society. This category includes 10% of all translations. This method is more common with publisher group 3. 24% of their translations belong to this category, compared with 6% of group 1 and 7% of group 2. One reason might be the large share of non-fiction in group 3 (90%), because this method seems to be used more often with non-fiction. In source language distribution there is one change compared to figure 3: Swedish and German have changed places, so Swedish books may be translated this way more often than others.

In one sense, the translations made from abridged texts are not abridged translations, because the source text is not shortened during the translation process. However, they can be included in abridged translations, because the source text (unabridged) and the translation are different, there is just one stage more in the process: the shortening of the source text in the source language. And the publisher could have chosen the unabridged source text, so it is a question of choosing to publish a shortened text.

11% of all translations belong to this category. This category includes a 6 percentage point share of children's fiction translated from English. These books are retellings of classics translated into Finnish, for example the ones published by Base-Beat. Because of this the source language distribution of this category differs considerably from the one in figure 3. I separated the classics translated for children this way and the classics translated for children using the first method from each other by using the original text given in the entry of the book in Fennica.

The 6 percentage point share of children's fiction affects also the publisher distribution. 79% of the translations in this category belong to the publisher group 1, and two of the publishers, SLEY-kirjat and Base-Beat, got to that group because of their translations belonging to this category. So it is better not to draw any conclusions about the publishers.

This method in which translation and abridgement are made by different Finnish persons, seems to be a reasonable one. The books treated this way are of special subjects, for example, strategic leadership, or communism in Finland 1944-48, and so it is maybe better to get someone who knows the subject well to do the shortening. At least I hope this is the reason for this kind of treatment. This category's share of all translations is the same as next one's: 3.5%.

Translations made from translations include translations made from abridged translations, abridged translations made from translations, and translations made from the original language, but abridged by using some other translation as a guide. The publisher group 1 has 75% share of these translations, and one possible explanation could be the dominance of fiction - 85% of translations in this category - because the publishers in group 1 publish relatively more fiction (67% of their translations) whereas groups 2 and 3 concentrate more on non-fiction, for which this method may not be suitable, because of the risk of errors.

To me this method seems to be the most dubious one, because it means relying on the other translator's choices when there could be better solutions. Sometimes, though, this method is more acceptable: if the source language is a very small one, or otherwise such that it is difficult to find a translator (for example, Japanese), it is maybe justified to use for example English version of the text. However, it would be better to use an unabridged translation, if that can be found.

Of all the 218 translations, only 15 included a statement that they were shortened with the permission of the writer. In addition, 1 was shortened in cooperation with the writer, and 2 translations were made from a text the writer had shortened. This means that 200 books were shortened without writer's permission or that the publisher did not care to mention whether the writer had given permission or not. Of course there are many books for which you could not ask the writer's permission even if you wanted to, because the writer is dead. This is the case especially for the classics.

I was interested in finding out if there were translators who have specialized in this kind of translation. Most of the 180 translators (the figure includes 12 translator pairs) who have made abridged translations have made only one or two of them. There are 7 translators who have done 4 or more abridged translations.

There are a couple of special cases worth mentioning, because they show some of the more unusual ways of translating. The first of these is a non-fiction translation to which translator has written two new chapters. In the second case the figures included in the book have been translated by one person, and the text by another. And finally, there was a book which was a shortened, edited, and translated version of a series of lectures.

Kirjavaliot published by Valitut Palat are not included in the figures I have presented for the same reason I made the difference between the peaks and real increases in chapter 2.3: it would have placed too much emphasis on one publisher and one particular series of books. It does not really say much about the general acceptability of the phenomenon, if one publisher is publishing a series of abridged translations. So I will deal with them separately in this chapter. Strictly speaking, Kirjavaliot are not abridged translations, but for the reasons explained in chapter 2.6.4, I chose to include them in this study.

Valitut Palat as a publisher really belongs to a group of its own as it has published 72 volumes of Kirjavaliot each containing 3 or 4 shortened books, about 250 books in total, during the period of 1980-1993. As I have already mentioned, the amount of other shortened translations was 218 for the period of 1960-1993.

The idea with Kirjavaliot is to have 3 or 4 shortened books bound into one volume. These translations belong to category 3 (see chapters 2.6.1 and 2.6.4), translations made from abridged texts. These books are translated into various languages from an abridged source text. It makes sense to shorten the original text before translating it as it saves time and money when you only have to do the shortening once. Also, this way the different translations correspond to each other better.

These books are very short compared to the originals. The idea of this shortening and bundling of the books is originally American, and the reason for it is probably the fact that many people do not have the time or patience to read the original, unabridged versions, and they are willing to buy these abridged versions instead. These books differ from other abridged translations in that in many cases there is another, unabridged translation the reader can choose. Approximately one book in each volume of 3 or 4 shortened books has not been translated into Finnish before. With other abridged translations, there often is not even this much choice.

In general the tendency seems to be towards avoiding abridged translations, though some publishers seem to accept shortened translations more easily. At least WSOY, Karisto and Valistus seem to reprint theirs unaltered again and again. However, the small percentage share of some of the major publishers seems to indicate that they have some reservations concerning these translations. In fiction/non-fiction aspect there seems to be no change. There has been varying amounts of both after 1960, without any clear tendency to avoid one or the other. An exception to this is Tammi.

There is one positive side in abridged translations, which can be seen when looking at the books published by those 41 publishers, who have published only one translation. The subject of the book can be very narrow, like alcohol problems at the work place, hashis problem from the point of view of the parents, or the views and beliefs of some small religious community. This kind of books would probably not attract any major publisher, and therefore would not be translated at all without the small publishers. Therefore, it is probably better to have the books published even in an abridged form than not at all, because it gives people access to these books.